Initial analysis from PHMSA incident reports

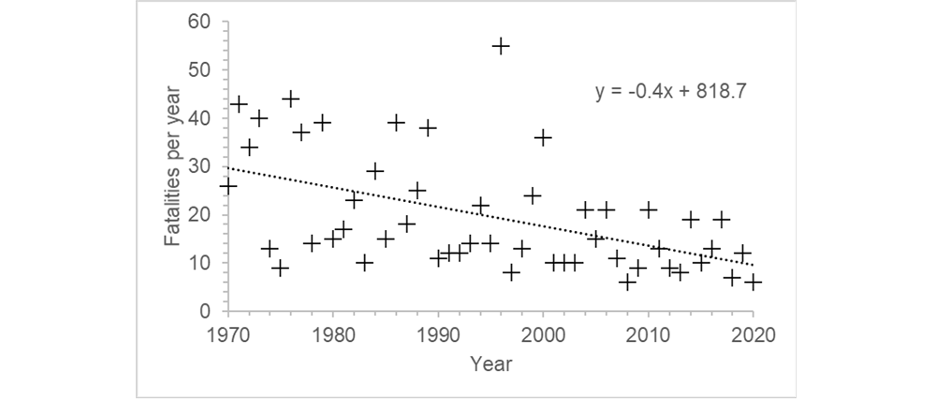

Since the 1970s, the total number of fatalities caused by all natural gas leaks have decreased from 30 to 9 (Figure 1).

From 2011 – 2020, subsurface leaks account for 52% of the leaks, 43% of all fatalities and 75% of operator fatalities (Table 1).

Table 1 Summary of the subsurface events in the PHMSA incident reports from 2011 to 2020, including total number of incidents, total fatalities, operator fatalities (including operator employees, contractor employees working for the operator and workers working on the right-of-way, but not associated with the operator), emergency first responder fatalities and general public fatalities.

| 2011-2020 | Incidents from available data | Total Fatalities | Operator Personnel Fatalities | Emergency First Responder Fatalities | General Public Fatalities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All events | 2,427 | 127 | 28 | 2 | 97 |

| Subsurface events | 1,257 | 54 | 21 | 1 | 32 |

| Subsurface % | 52 | 43 | 75 | 50 | 33 |

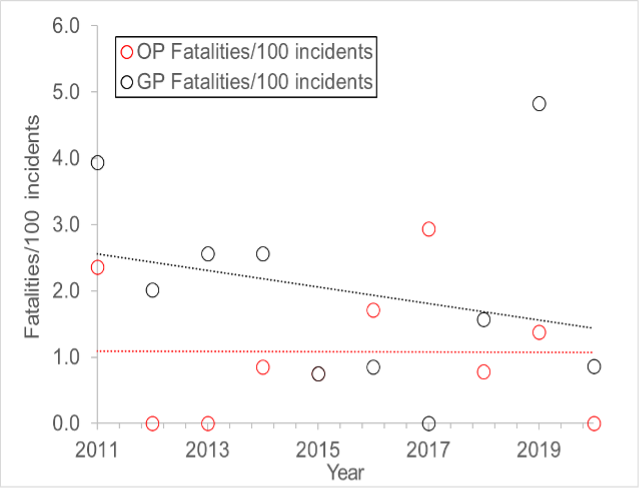

In the last 10 years, fatalities to the general public have decreased but there has been no change in annual fatality rates in operator employees (Figure 2).

While the cause of operator fatalities is complicated (fires at the leak, explosions, and asphyxiation), 90% of general public fatalities were caused by houses exploding and 30% of house explosions happened after the emergency services had arrived at the scene. At present there is no clear understanding of how long it takes a house to explode or any evidence-based approach to calculating exclusion zone (one block is used as a rule-of-thumb). It is suggested that the METEC experiments can be used to better understand the time it takes for leaked gas in houses to reach explosive concentrations and calculating safe exclusion zones, both of which are determined by the environmental conditions and locations of the house.